The Tragic Sense of Life: Unamuno’s Human Faith

Unamuno’s The Tragic Sense of Life explores how reason and faith, despair and hope, collide within the human soul, and why our struggle to live while knowing we must die is the source of our dignity. He writes as a man wrestling with his soul; philosophy as faith against despair.

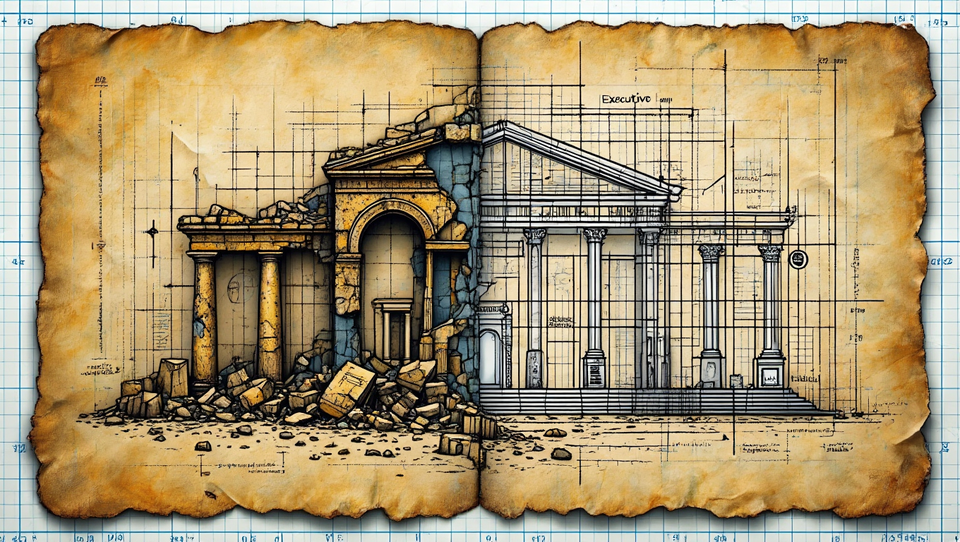

Miguel de Unamuno’s The Tragic Sense of Life (1912) is not so much a treatise as a spiritual confession. It stands as one of the most intense efforts in modern philosophy to unite intellect with passion, faith with doubt, and philosophy with life. Written in the long shadow of nineteenth-century rationalism and in the dawn of Europe’s disillusionment, Unamuno’s book insists that philosophy must begin and end with the “man of flesh and bone”, not with abstractions about humanity, but with the mortal being who eats, loves, suffers, and dies.

At the heart of Unamuno’s work lies a simple but devastating question: how is a thinking being to live in full awareness of death?

His answer, though anguished, is heroic. The meaning of life, he argues, arises not from reconciling faith and reason but from enduring their conflict. The tragedy of human existence, the knowledge that we must die and cannot accept it, is also its glory.

The man of flesh and bone

Unamuno begins by rejecting the philosopher’s tendency to treat humanity as an idea. “I am a man,” he writes, “no other man do I deem a stranger.” Against the “featherless biped” of Aristotle or the rational animal of Descartes, he sets the concrete person: the embodied, suffering, desiring self. Philosophy, he argues, too often forgets that the thinker is a man who will die. In most philosophical systems, doctrines replace lives; “the inner biography of the philosopher,” Unamuno laments, “is forgotten.” Yet it is precisely the hidden drama of the philosopher’s soul that gives birth to thought.

Kant’s “somersault,” from the Critique of Pure Reason to the Critique of Practical Reason, becomes for Unamuno an emblem of this buried humanity. The German sage demolishes the traditional proofs of God, only to re-establish faith on moral grounds. Reason denies; the heart restores. Unamuno sees in this not inconsistency but authenticity—the human refusal to accept meaninglessness. Kant, like all men, could not resign himself to die utterly. Reason may speak of necessity; life demands hope.

Faith born of contradiction

Unamuno’s central insight is that faith is not a deduction but a rebellion. It is the revolt of the living being against extinction. The “tragic sense of life” names the condition of a mind that knows its arguments against immortality are sound yet still cannot help believing. For Unamuno, the soul’s longing to endure is not a childish wish to be comforted but the very essence of consciousness. To live truly is to refuse annihilation.

In this defiance, Unamuno stands closer to Kierkegaard than to Spinoza. Against the rational serenity of the Dutch philosopher, who saw the human striving to persist as part of an impersonal substance, Unamuno insists that the struggle itself, the desperate clinging to personal being, is what makes us human. Spinoza’s “God intoxication,” he says, was really the symptom of a “God-ache,” the ache of a man who could not quite believe in his own immortality.

Where reason seeks coherence, life seeks continuity. The intellect demands truth, but the heart demands meaning. To Unamuno, these two demands cannot be reconciled, yet both are indispensable. If we surrendered reason, we would lose our dignity; if we surrendered hope, we would lose our will to live. Thus the tragic sense of life is not despair but tension, a dynamic equilibrium between doubt and faith. “Our faith,” he writes, “is born of our desire for eternal life; and our reason kills what it touches. But to live is to be at war with reason.”

The creative will and the making of God

Unamuno’s answer to this conflict is not resolution but creation. From the depths of uncertainty, man must fashion meaning. Out of his hunger for eternity, he invents God—not as an illusion, but as an act of love. “If there were no God, we should have to create Him,” he affirms, echoing Voltaire but reversing the irony. For Unamuno, God is not a distant cause or a logical necessity; God is the name we give to the universe once it becomes conscious through our suffering.

This theology is profoundly humanistic. Man and God are mirrors of one another: our will to persist becomes God’s creative power. To believe in God is, therefore, to affirm the sacredness of personality itself. Love, the act of recognizing another as irreplaceable, extends our finite being into the infinite.

When we love, we grant the beloved a kind of immortality in our own consciousness. Love, pity, and the yearning to save others from oblivion become the highest moral acts because they are the ways we participate in eternity.

In this way, Unamuno reinterprets the Christian virtues. Faith is not certainty but the courage to hope; hope is faith in the midst of contradiction; charity is the active sharing of the tragic struggle to exist. Even despair, if it deepens our compassion, can serve the divine.

The true religion, he suggests, is not a doctrine of peace but a fellowship of anguish.

The religion of struggle

Because death cannot be abolished, life becomes an ethical challenge. Unamuno urges us to “make ourselves irreplaceable,” to live in such a way that our disappearance would be an injustice to the universe. Work, creativity, and moral effort are forms of resistance against annihilation. “Conflict,” he writes, “is the basis of conduct.”

The tragic sense of life, therefore, yields an ethic of struggle, not the calm of the sage but the restless heroism of one who acts despite knowing he will die.

This ethic extends to the social realm. Against the collectivist ideologies of his time, Unamuno defends the sacredness of the individual soul. Society exists for the person, not the person for society. Yet his individualism is not selfishness; it is rooted in the conviction that the fate of all depends on the salvation of each.

Only the person who asserts his immortality can truly love his neighbor.

Don Quixote and the dignity of folly

In the book’s final chapters, Unamuno turns to Spain’s national myth, Don Quixote, as the embodiment of the tragic faith. The knight of La Mancha, who fights for ideals the world deems absurd, becomes for Unamuno the model of spiritual courage. Quixote’s madness is not delusion but sanctity—the refusal to accept a world stripped of meaning. He is the “man of faith” in an age of skepticism, one who lives as though his dreams were real because to do otherwise would be to die inside.

Through Quixote, Unamuno transforms Spain’s comic hero into a universal symbol of existential defiance. The modern world, obsessed with progress and reason, he saw as spiritually sterile. What it needed was not more “culture” but more soul.

“Don Quixote fought for the spirit,” Unamuno writes, “not for ideas.” His mission is ours: to affirm life in the face of death, to turn absurdity into dignity, and to love even when reason says love is futile.

The modern saint of anguish

Salvador de Madariaga, in his introduction to The Tragic Sense of Life, called Unamuno “a knight-errant of the spirit.” The phrase captures both his pathos and his power. Unamuno lived as he wrote: passionately, combatively, unable to separate intellect from emotion. His thought was not systematic but a struggle, not a theory but a confession. Like his beloved Quixote, he fought windmills of reason with the sword of faith, and knew they were windmills; yet he fought on.

What Unamuno offers modern readers is not consolation but courage. In an age that oscillates between cynical disbelief and shallow optimism, his voice reminds us that meaning is forged, not found. To live authentically is to accept the full weight of mortality and yet to act as if eternity depends upon us.

In this sense, Unamuno’s philosophy is both profoundly religious and profoundly human. He teaches that to be a person is to live in contradiction: to think and yet to love, to doubt and yet to hope, to die and yet to yearn for immortality. The tragic sense of life is the condition of consciousness itself: the wound by which we know we are alive.

Conclusion

Miguel de Unamuno’s The Tragic Sense of Life remains one of the most passionate affirmations of the human spirit in modern literature. It refuses the easy peace of either dogma or nihilism, insisting instead that our very conflict, between faith and reason, love and death– is the source of our dignity. We are beings who cannot bear to die, yet must. Out of that impossibility, Unamuno finds the meaning of life.

To live, then, is not to resolve the tragedy but to embrace it, to keep thinking, hoping, and loving even as the night closes in. “Our thirst for immortality,” Unamuno wrote, “is the tragic root of our existence.” It is also, he believed, the only thing that can make us whole.

Peter Thiel vs. Miguel de Unamuno: The Big Question

In contrast, Billionaire Peter Thiel views death as "a bug in the program" that must be fixed through technology.

He criticizes society for passively accepting mortality and argues we need radical ambition, pointing to AI, Mars colonization, and life extension as ways to escape civilizational stagnation.

Miguel de Unamuno argues the opposite: that our awareness of death, and our refusal to accept it emotionally even while knowing it rationally, creates the "tragic sense of life" that is the very source of human dignity and meaning.

For Unamuno, we must not resolve this tension but live within it, making ourselves "irreplaceable" through love, creativity, and moral struggle.

The Question: Who is right?

Is Thiel's technological fight against death an attempt to escape from the existential struggle that Unamuno says makes us fully human? Is Theil denying his own humanity? In my opinion, you can't solve meaninglessness by adding more time.

Dennis Stevens, Ed.D.

Writer and civic designer exploring the intersection of governance, technology, and moral architecture. Thought-leader and steward of agoradao.eth on the Blockchain, publishing also at mirror.xyz/agoradao.eth.